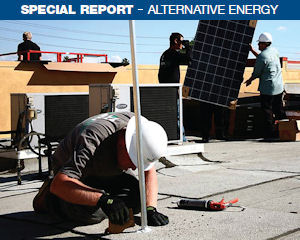

The Valley has its share of high-tech companies exploring the outer edges of the solar market, but if there is one dominant segment of the industry it’s still the relatively low-tech solar panels being installed on the roofs of homes and businesses. And it’s not just one-off installations that are driving the market anymore. Entire subdivisions are being built in the Antelope Valley with solar-paneled homes, while Wells Fargo & Co. has decided to install solar panels on three of its L.A. branches, including two in Van Nuys. Xiomara Roman, vice president at Lancaster solar installation company So-Cal Solar Inc., said she has witnessed an explosion in the number of solar panels residential and commercial customers have had installed in the last two years. “This last year has been a heavy focus on the commercial side of installation,” Roman said. “At the end of the day it makes sense.” The installations are being driven by the lower cost of panels as inexpensive Asian imports have flooded the market, though panel installers such as So-Cal Solar are usually unwilling to discuss their retail costs for competitive reasons. According to a recent report by Near Zero, an alternative energy education group based in Stanford, Conn., the costs of solar modules – the basic core of a solar panel that converts sunlight into electricity – fell by half between 2005 and 2010 to $2 a kilowatt hour. Prices are expected to continue to fall, but current prices are still not competitive with electricity derived from fossil fuels. However, coupled with local rebates and the solar Investment Tax Credit from the federal government, solar energy can make economic sense. The Los Angeles Department of Water and Power’s rebates can cover up to 50 percent of installation costs for commercial customers, depending on how much energy a system generates. The federal credit covers 30 percent of costs. “There’s an ease to getting solar installed in the market that’s never been there before,” said Eric Wesoff, senior analyst and editor of Greentech Media, a Boston-based research group that covers the environmental industry. Declining incentives However, the rebates and tax credit programs are expected to run out unless they are renewed, which would slow installations of solar panels. For example, a LADWP rebate program begun five years ago was funded with $313 million. The funds are available through the end of 2016, or until the money runs out, which could be far sooner. There is only about $52 million left in residential funds, and $10 million for commercial customers, said Anh Wood, solar program manager at the municipal utility. In July, the department began accepting applications for rebates to be paid out through June of next year and funding ran out in 19 minutes. The department has confirmed 92 installations so far for its 2012 fiscal year for commercial solar panel users in addition to 1,400 residential applications. Wells Fargo decided to install panels in April after customers encouraged the bank to do so, said Jason Vasquez, a bank spokesman in Los Angeles. “We saw an overwhelmingly positive response from our customers,” he said. The local Wells Fargo branches were unable to receive LADWP rebates, but the company will still receive a federal investment tax credit. The panels are expected to produce 41 kilowatts of electricity a year, or about 30 percent of energy use at the three branches. The panels were installed by Verengo Solar, which is based in Phoenix but has a local affiliate in Torrance. They should last about 25 years before replacement. Stephanie Rico, vice president of environmental affairs for Wells Fargo nationwide, said that the company hasn’t decided yet whether it will install more panels because it’s too soon to tell whether or not doing so is feasible or economically viable. “We’re assessing the situation,” she said. “There are a lot of factors involved, and it’s not as easy as putting solar panels on every rooftop.” One issue is the structural soundness of each building, with older buildings more difficult to work on than newer ones. It’s also more difficult for the bank to install panels on buildings it leases rather than owns. The three branches which got panels are owned by the bank, Vasquez said.