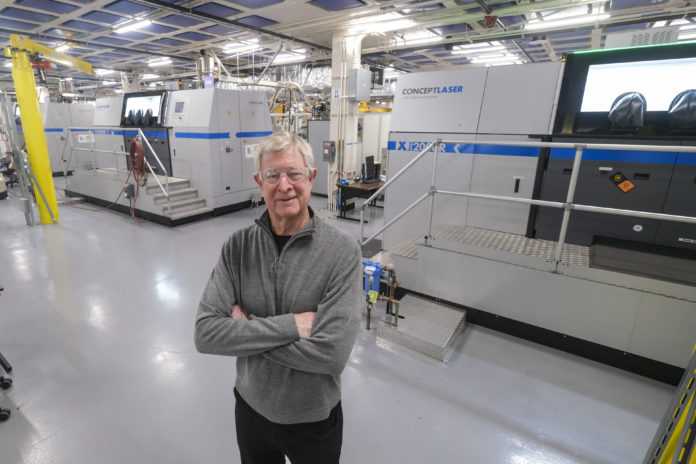

Doug Bradley walks through the factory shop floor at Aerojet Rocketdyne in Chatsworth pointing out the equipment used to make rocket engines.

Bradley is the deputy director of the RS-25 program, which is building the engines used on NASA’s Space Launch System, the heavy rocket that takes humans to the moon and on other deep space missions.

Last year, the factory underwent a nearly $60 million expansion, primarily to support the RS-25 program.

“We were able to have the manufacturing people lay out the whole factory, so it flowed a lot better. It is a more efficient factory,” Bradley said. “It is a smaller footprint, but we can do a lot more with it.”

The aerospace industry is still a major one in the San Fernando, Santa Clarita and Antelope valleys. It encompasses the big players, such as Aerojet Rocketdyne, Northrop Grumman Corp. and Lockheed Martin Corp., the latter two with facilities in Palmdale, down to the small machine shops that do work for the big boys.

According to a 2016 study by the Los Angeles County Economic Development Corp., the Southern California aerospace industry brought in about $40 billion in revenue in 2014. Southern California is made up of eight counties stretching from Kern down to San Diego.

“Of this, aircraft accounted for the most sales, reaching $12.9 billion, or almost one third of all output. Instrumentation accounted for $11 billion, or 27.5% of the total, while aircraft parts accounted for $8.5 billion. The value of production of guided missile and space vehicles and their related parts reached $6.5 billion in 2014,” according to the study, done in conjunction with the San Diego Regional EDC.

About 246,000 direct, indirect and induced jobs were created by the aerospace market in Southern California in 2014, a number that includes commercial, military and civilian employees, the LAEDC report found.

“Most people don’t realize this, but aerospace is larger than agriculture and entertainment combined in its annual economic impact,” said Mark Taylor, director of state government operations for the Chicago-based Boeing Co. In his role, Taylor helps manage the state and local government relations work and corporate giving in California.

When it comes to jobs, Aerojet Rocketdyne, a subsidiary of Aerojet Rocketdyne Holdings Inc., in El Segundo, is in hiring mode.

According to Jesse Basarab, a spokesman for the company, approximately 100 to 150 people were onboarded this year alone in Chatsworth. Aerojet currently has between 100 and 200 openings posted on its website, he added.

The Chatsworth facility employees around 1,200 personnel.

Last month, Melbourne, Florida-based L3Harris Technologies Inc. announced it was acquiring Aerojet Rocketdyne in an all-cash deal valued at $4.7 billion. The transaction is expected to close this year, subject to regulatory approvals and clearances and other customary closing conditions.

The following is a roundup of other aerospace companies in the greater Valley region.

Top employers

Tim Frei, vice president of research and advanced design in the aeronautics systems division of Northrop Grumman, said that people often lose focus on what the company is doing up in Palmdale.

The Antelope Valley factory, located on Air Force Plant 42, is where the Falls Church, Virginia-based aerospace and defense contractor produces the center fuselage for the F-35 Lightning II, a single-seat, single-engine stealth fighter built by Lockheed Martin.

“Just a few weeks ago we celebrated the delivery of the 1,000th center section,” Frei said.

Palmdale is also where the Global Hawk unmanned aircraft and its variant, the Triton, are built, along with the two X-47 prototype aircraft that were the first to autonomously take off and land on an aircraft carrier. It is also the location in which maintenance and upgrades are made to the B-2 Spirit stealth bomber.

And the new program for Northrop in Palmdale is the B-21 Raider, the Air Force’s latest stealth bomber, which was unveiled to the public on Dec. 2.

“The B-21 Raider defines a new era in technology and strengthens America’s role in delivering peace through deterrence,” Kathy Warden, chief executive of Northrop, said in a statement.

Frei said that Los Angeles-area operations are forecast to continue to grow in coming years, thanks to programs like the B-21 and other developmental aircraft.

“The work on the B-21, as that program transitions from development into low-rate and eventually full-rate production, we see increases there,” he added. “We see the F-35 continuing as a program of record. Those are the two major activities in Palmdale.”

With more than 7,000 employees in Palmdale, Northrop is among the top employers in the Antelope Valley area.

And the company is doing what it can to make sure there are always workers ready to relocate there and build and service aircraft.

In 2020, it launched its ASTAR Academy, which stands for Aeronautics Systems Training for Advanced Refinement. Located adjacent to Northrop’s factory at Plant 42, the academy provides hands-on training for aircraft mechanics, Frei said.

“They are trained as technicians in various areas, whether it is manufacturing, flight test, quality control,” Frei said. “Since 2020 we have graduated more than 1,000 students from our ASTAR Academy.”

The company also has a partnership with Antelope Valley College for a training program in advanced composite-aircraft development.

And finally, there is HIP, or the High School Involvement Partnership Mentoring Program, which Northrop developed with area schools.

“It was a program created to inspire high school students for science, technology, engineering and math pathways to fill future workforce needs in that region,” Frei said.

There seems to a continued demand for all the programs that Northrop has developed, and they continue to get qualified candidates, he continued.

“We are training them as quickly as we can and putting them on the production floor,” he added.

Skunk Works

At Lockheed Martin’s Skunk Works facility in Palmdale, secrecy is the name of the game.

There are, however, some accomplishments at the site that are discussed publicly, one example being the Stalker VXE drone, which in February reached a world-record endurance flight at Santa Margarita Ranch.

According to a release from Lockheed, the flight established a new record of 39 hours and 17 minutes for drone planes weighing between 5 kilograms and 25 kilograms.

The flight has been submitted to the Fédération Aéronautique Internationale, the world sanctioning body for aviation records, through its U.S. affiliate, the National Aeronautic Association, for certification, according to the release.

In late November there was an announcement that the Skunk Works had successfully integrated a 5G core and open radio access network, often called O-RAN, into the company’s 5G.MIL hybrid base station.

John G. Clark, vice president and general manager of Skunk Works, said that the company’s 5G.MIL station was designed using open mission-systems standards, meaning the technology can onramp to multiple platforms quickly.

“The integration of 5G and military tactical radios into our hybrid base station enables resilient, link-diverse data routing throughout the battlespace to make future crewed-uncrewed distributed teaming missions possible,” Clark said in a statement.

By implementing the base station within a 3U/VPX (three rack units/virtual path cross-connect) form factor, Lockheed demonstrated over-the-air 5G and tactical network connectivity in a lab environment capable of being used in military aircraft, the company’s release said.

“While most applications of 5G base station technology are data center-centric, this demonstration hosted 5G O-RAN technology on ruggedized computers suitable for fighter and other aircraft, paving the way for the team to fly on any number of military platforms during upcoming crewed-uncrewed distributed teaming flight tests,” the release said.

3D printing

Meanwhile, back at Aerojet Rocketdyne, Bradley looks in on a 3D printer that is making a part for the RS-25 engine.

These printers are what Bradley is most excited about these days.

“This is taking hardware that used to take months to build, and we make it in weeks, or used to take weeks and making it in days,” he said.

Aerojet has about 35 parts on the new engines that are fully 3D printed, including one that used to be made up of 40 parts and has been consolidated into two, he said.

The 3D printing helps lower the costs of the engines, which Bradley would not disclose.

“Suffice to say, they are too expensive right now to sustain the program, so we have to make them cheaper,” Bradley said.

Under a directive from NASA to make the engines 30% less expensive, Bradley said that Aerojet had come up with different ways to achieve that goal.

One is 3D printing, while another is the use of machining centers, or machines that can turn, mill and grind a piece of metal without the metal having to be moved from machine to machine.

“That really cuts out a lot of time,” he said.

While it is approaching the 30% cost-reduction mandate, the company has designs in development that will get it to a 50% cost savings.

To achieve that will mean improving the rocket’s nozzle, which Bradley described as being the part of the engine that most people are familiar with because it sticks out from the bottom of the rocket.

It is also the most difficult and most time-consuming piece of the engine to produce, he added.

“We are going to cut the cycle time – how long it takes to build it – in half,” Bradley said.

To reach that goal will mean having to use 3D printers for the nozzle.

“It won’t be in one of those machines (that he looked in on earlier),” Bradley continued. “There are different ways to 3D print. It will be different 3D printing. We already have models that we have built.

Currently, the way to make a nozzle involves a lot of automation supplemented by some manual labor, namely with the 1,080 coolant tubes, which must be placed by hand.

Just as a car’s engine must be cooled, the rocket’s nozzle, which can reach a temperature of 6,000 degrees in its forward end, needs to be kept at safe operating temperatures.

“We use the fuel from the engine, which is really, really cold, at about minus 420 degrees, and we’ll put it in a manifold, and these tubes are attached to the manifold to cool it down,” Bradley explained. “That is what helps the nozzle to survive.”

According to the aerospace report from the LAEDC, California has many attributes that the industry continues to draw on.

These include ideal climate conditions for flight-testing, large, restricted airspace, a deep labor pool fed by numerous colleges and universities and an emerging startup scene.

Still, aerospace employment is the state is less than half of what it was in 1990 due to the end of the Cold War. But a loss of employment does not imply a dying industry, the report said.

While experiencing significant declines in employment, the aerospace industry has maintained its sales and revenue, the report found. This comes from innovation and advancements in technology and increases in productivity, efficiency and automation.

“Once home to numerous facilities manufacturing conventional airplanes, today the majority of growth in the industry lies in drone development and space-related technologies,” the report concluded.