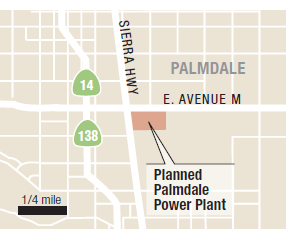

Earlier this month, the Palmdale City Council voted to sell the rights to build a power plant in town to a Seattle company for up to $27.4 million. At first glance, that sounds like a nice chunk of change. But the Antelope Valley city is actually just about breaking even on what it has invested so far in the proposed project. In 2005, the city began moving forward with plans to build a hybrid solar power plant to take advantage of the high-desert city’s abundant light, hoping to work with a developer on a long-term partnership. But as solar energy became less competitive with natural gas and as complications piled up, the city began looking for outside developers to take over the project. Still, if Summit Power Corp. eventually builds the 570 megawatt plant – now to be powered by natural gas turbines – the city will be counting its blessings. “We’re really happy with this,” said Director of Public Works Mike Mischel. “We think they’re serious about getting it done and that this will finally happen.” The initial proposal was pegged to cost nearly $1 billion, but Mischel said that cost may be lower if Summit removes the solar component. During the estimated 27 months of construction, the plant will employ as many as 800 construction workers, with roughly 30 employees staying on full time. The city also wants Summit to locally source some component parts and supplies. There are other reasons the city is counting itself lucky. Consider neighboring Victorville. The nearby San Bernardino County city began work on two natural gas plant nine years ago, and funded part of the work with municipal bonds. But with the recession, the project stumbled. Now Victorville is deep in debt and until February was entangled in a long-running civil battle with a former consultancy on the projects. “Cities are under a lot of pressure, budgetary pressure, as state and federal funding dry up,” said Sachu Constantine, director of policy for the California Center for Sustainable Energy. “They don’t want to end up stuck with a costly capital outlay. I understand the motivation to sell and recoup their costs.” Palmdale got into the energy business in 2003 when it purchased 615 acres of desert land from aerospace firm Lockheed Martin Corp. for $18 million. The idea was to build a hybrid plant with a mix of solar-thermal and natural gas power. It partnered with Newport Beach consulting firm Inland Energy LLC, and began funding environmental reports, studies and permit applications. At the time, the city estimated that the plant would break ground in 2011 and be running by 2012, generating enough electricity to power the city and have some left over to sell back to the grid. But delays abounded as the California Energy Commission questioned air quality issues stemming from the planned natural gas turbines and sent the city back for additional studies. Palmdale had gone through the approval process without a development partner, but it saw by last summer that it wasn’t going to be feasible to go it alone. At that point, it began contemplating selling off the permits it had spent $10 million to acquire rather than take a long-term stake in the project with a commercial partner. By October, the city sent out 50 official requests for proposals to alternative energy developers looking to take over the project – and willing to take on Inland Energy as a partner, another contractual obligation the city was under. Palmdale received about six formal proposals, and culled through them throughout the winter, according to Mischel. The final decision was made to walk away from the project and sell off the permits, which have a shelf life of roughly five years before costly extensions are required. The company has built hybrid projects nationwide, including several approved in California. It has completed solar, natural gas and wind projects, often combining those options into hybrid developments. Summit is acquiring just 50 of the 615 acres the city bought in 2007, leaving 515 acres for other development. It has an option on an additional 50 acres. Summit says it is eager to get underway on the project, although it declined to give details on the expected start dates. “We look forward to working with the city to finally bring this power project to fruition,” said Tom Cameron, a principal at Summit Power, in a statement to the city council. According to a city staff report, the company must meet building milestones over the next one to two years. Breaking ground The city has not completely walked away from the project, though. It will still work with the developer to assist in additional permitting and power-purchase agreements, as well as transmission lines for the power. Inland Energy, which has been with the project since the beginning, is now contracted to help Summit. This approach is consistent to what is being done in adjacent Lancaster, where the city has brought in alternative energy projects, but has given the projects to private developers, with the city focusing its energy on shepherding the projects through government channels and approvals. It’s attracted more than a dozen developments, and touts itself as the state’s solar capital. Still, completion of the plant is not a sure bet. Before the project can proceed, it will need approval from the Antelope Valley Air Quality Management District, which will be more difficult now that the plant is all gas. As a hybrid model, the solar component of the plant would be easier to move through, as much of the approvals hinge on required emissions offsets – something solar panels can provide. The alternative is to buy emission credits that are traded on a market. Lancaster Councilman Marvin Crist, chairman of the air district, estimates that the credits will cost $15 million for the total plant build. “Palmdale would have to pay $15 million. They haven’t found a way to do that yet,” he said. Mischel noted that the city is working on some projects to mitigate those required credits, including paving over dirt roads, which minimize dust particulates in the air. He said Summit will also have to go before the California Energy Commission to get the permits altered if it abandons the solar component, which it has indicated it will do. The city will play some role in that as it is currently the holder of the permits. But whatever it still has to do, the city should end up better off than Victorville. With only one of two proposed plants in operation, Victorville spent millions on equipment for the second plant that never went into operation. And it is under investigation by the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission over the millions of dollars in bonds it issued to fund the projects. Palmdale officials say that was a lesson they take to heart. “They were looking to self-manage,” Palmdale Mayor Jim Ledford told the Business Journal when the city decided to look for a developer. “We won’t do that. That’s what got them into trouble.”